Sète, France: The Venice of Langedoc

Where Canals Meet the Sea

Sète doesn't get the attention it deserves, and perhaps that's part of its charm. Tucked along France's Mediterranean coast between Montpellier and the Spanish border, this working port town of faded pastel facades and crisscrossing canals has somehow escaped the glossy makeover that transformed much of the French Riviera. Here, fishing boats still matter more than yachts, oyster farmers work the Thau Lagoon as their families have for generations, and the scent of grilled seafood drifts from harborside restaurants where locals far outnumber tourists.

Built on and around Mont Saint-Clair—a limestone outcrop that rises dramatically from the flat Languedoc coastline—Sète straddles a narrow strip of land between the Mediterranean Sea and the vast Étang de Thau. This unusual geography has shaped everything about the city. Canals slice through its center like watery boulevards, their bridges painted in shades of ochre and blue. Fishermen moor their boats directly beneath apartment windows. The town climbs the slopes of Mont Saint-Clair in terraces, offering views that sweep from the Pyrenees to the Cévennes on clear days.

Founded in 1666 as the Mediterranean terminus of the Canal du Midi, Sète has always been a place of arrivals and departures, a crossroads where Catalan, Italian, and North African influences blend into something distinctly its own. The poet Paul Valéry was born here and is buried in the maritime cemetery perched above the sea—the same cemetery that inspired his meditation on mortality and the Mediterranean's eternal rhythms. Georges Brassens, the beloved French singer-songwriter, also called Sète home, and his legacy still echoes through the port's bars and festivals.

This is a town that lives by the water and the rhythms of the sea: the morning fish auction at the Criée, the summer joutes nautiques (water jousting tournaments) that have crowds roaring along the canals, the endless procession of boats moving between lagoon and open water. Sète invites you to slow down, to linger over platters of shellfish and chilled Picpoul de Pinet, to wander streets that dead-end at water, and to discover a France that feels both timeless and lived-in—a rare combination along this increasingly polished coast.

A Sculptural Escape: The Saint-Martin Gardens of Monaco

Just a short journey along the coast from Villefranche-sur-Mer brings you to Monaco, where the Saint-Martin Gardens offer a tranquil escape from the principality's glitz and glamour. Perched on the cliffs of Monaco-Ville (the old town), these gardens wrap around the Oceanographic Museum and Prince's Palace, providing one of the most serene and artistically enriching experiences in the city-state.

What makes the Saint-Martin Gardens truly special isn't just the manicured Mediterranean landscaping or the stunning views over the sea—it's the extraordinary collection of outdoor sculptures that transform the space into an open-air museum. As you wander along the winding pathways shaded by ancient olive trees, towering pines, and graceful palms, you'll encounter striking works of art that seem to emerge organically from the lush greenery.

Among the garden's most captivating pieces are the bronze and stone sculptures that dot the landscape. One particularly beautiful bronze figure stands draped in contemplation, her verdigris patina blending harmoniously with the vibrant red geraniums and golden foliage surrounding her base. The weathered stone pathway beneath creates a sense of timelessness, as if this figure has been keeping watch over the gardens for centuries. Nearby, a more abstract stone sculpture with angular, modernist forms creates a dramatic contrast—a faceless figure balancing vessels, caught in an eternal pose against the backdrop of the Maritime Alps rising in the distance.

These aren't just decorative additions; they're carefully curated works by renowned artists that invite reflection and dialogue with the natural setting. Each sculpture is positioned to take advantage of the garden's dramatic topography—some overlooking the vast Mediterranean, others nestled in intimate alcoves surrounded by oleander, lavender, and rosemary.

The gardens themselves are a masterclass in Mediterranean landscaping. Succulents and cacti thrive in the rocky terrain, while fragrant herbs perfume the air. Stone benches positioned at strategic viewpoints invite you to pause and take in the panoramic vistas: the sparkling harbor below filled with superyachts, the azure sea stretching to the horizon, and on clear days, the Italian coastline in the distance.

What I loved most about the Saint-Martin Gardens was how they offered a quieter, more contemplative side of Monaco. While the casino and yacht clubs below buzz with energy and excess, up here in the gardens, art and nature create a space for peaceful wandering and discovery. The interplay between classical and contemporary sculpture, formal garden design and wild Mediterranean flora, creates an atmosphere that's both refined and refreshingly unpretentious.

Entry to the gardens is free, making it an accessible highlight for any Monaco visit. Whether you're an art enthusiast, a garden lover, or simply seeking a peaceful spot to escape the crowds, the Saint-Martin Gardens provide a cultural and natural oasis where beauty takes many forms—sculpted in bronze and stone, growing from the earth, and stretching endlessly across the sea.

Wandering Sète: A Town ‘Painted’ in Water and Light

The best walks in Sète follow water. Not the Mediterranean, which crashes against the breakwaters and sandy beaches on the town's southern edge, but the canals—the Royal Canal and the network of smaller waterways that thread through the center like liquid streets, reflecting sky and stone in equal measure.

Start at the Grand Canal, Sète's watery main artery, where painted fishing boats line both banks in a jumble of blues, reds, and sun-faded yellows. The Quai de la Marine hums with morning activity: fishermen mending nets, dock workers loading crates, café owners hosing down sidewalks. Cross any of the arching bridges—Pont de la Civette, Pont des Quilles—and pause mid-span. From here, the canal stretches in both directions, boats creating perfect mirror images in water so still it looks like glass until a passing vessel sends ripples radiating outward.

The buildings along the canal wear their age gracefully. Five-story townhouses in peeling pastels—dusty rose, faded yellow, weathered terracotta—lean slightly toward the water, their shutters thrown open to catch whatever breeze comes off the lagoon. Laundry hangs from wrought-iron balconies. Cats prowl the quayside. This is working-class elegance, beauty born from function rather than decoration.

Wander inland from the Grand Canal and Sète reveals its intimate scale. Narrow streets climb toward Mont Saint-Clair, staircases appearing where the gradient gets too steep for roads. The Quartier Haut, perched on the hillside, feels almost village-like—neighbors call to each other from windows, corner épiceries display locally caught fish alongside vegetables from nearby farms, and tiny squares with centuries-old plane trees offer shade and a place to rest.

The ascent to Mont Saint-Clair is worth the effort, whether you walk or drive the winding route. At 175 meters, the summit provides a geography lesson in a single view. Below, Sète spreads across its slender peninsula, canals glinting like ribbons. To the west, the Étang de Thau stretches vast and shallow, dotted with the geometric lines of oyster and mussel beds. To the east, the Mediterranean extends to infinity. And threading through it all, the thin strip of sand and scrub called the Lido, separating salt water from salt water, sea from lagoon.

Back at sea level, the Vieux Port pulses with life in the late afternoon. This is where the water jousting happens in summer—Sète's ancient sport where competitors stand on platforms at the front of boats and try to knock each other into the canal with long lances, cheered on by crowds packing the quays. Even without a tournament, the port captivates: trawlers returning with their catch, pleasure boats jostling for mooring space, the constant ballet of vessels moving through the narrow channel toward the lagoon.

Follow the Quai Maréchal Joffre along the port's edge and you'll find yourself in restaurant territory. Tables spill onto the sidewalk, menus scrawled on chalkboards promise the day's catch—daurade, loup de mer, mussels from the Thau. The local specialty is tielle sétoise, an octopus pie with Spanish roots that speaks to Sète's position as a cultural crossroads. Order it with a glass of local white wine and watch the boats drift past.

The maritime cemetery, perched on a hill overlooking the sea, offers a different kind of walk—contemplative, beautiful, tinged with melancholy. Paul Valéry's grave sits near the top, marked simply, his final resting place commanding a view of the water that inspired his most famous poem. The cemetery terraces down the hillside, white tombs catching the fierce Mediterranean light, cypress trees standing like dark exclamation points against the blue. It's both morbid and life-affirming, this place where Sète's dead continue to look out at the sea.

Walking Sète, you realize the town's magic lies in its refusal to choose between working port and charming destination. It remains both, unapologetically, the canals carrying fishing boats past café tables, the smell of the sea mingling with grilled seafood, the light bouncing off water at every turn. It's a place that asks nothing of you except to slow down, to notice, to let the rhythm of tides and boats and daily life wash over you like the gentle lap of canal water against ancient stone.

Les Halles: Where Sète's Soul Lives

If you want to understand Sète, go to Les Halles before nine in the morning, when the covered market is still in full roar and the day's catch hasn't yet sold out. This is where the town's identity as a working fishing port becomes visceral—not a romantic notion but a loud, pungent, gloriously messy reality.

The market hall itself is utilitarian rather than charming: a metal-roofed structure that could be mistaken for a warehouse if not for the crowds flowing through its entrances. Step inside and your senses get ambushed. The air is thick with brine and crushed ice, fish and shellfish, the mineral smell of oysters just pulled from the Thau Lagoon. Vendors shout prices and banter with customers in the melodic accent of Languedoc, their voices echoing off the high ceiling. Water sluices across tile floors. This is not a market designed for Instagram—it's designed for selling serious quantities of seafood to people who know exactly what they're looking for.

The fish stalls command center stage, their displays almost obscene in their abundance. Whole daurade gleam silver-pink on beds of ice. Monkfish tails lie thick as a man's thigh. Octopus tentacles curl in elegant spirals. Red mullet, sea bass, John Dory, and dozens of species most visitors can't name are arranged with the casual artistry of people who handle fish for a living. The vendors—many of them third or fourth generation fishmongers—can tell you not just what's fresh but where it was caught, what time the boat came in, how to cook it.

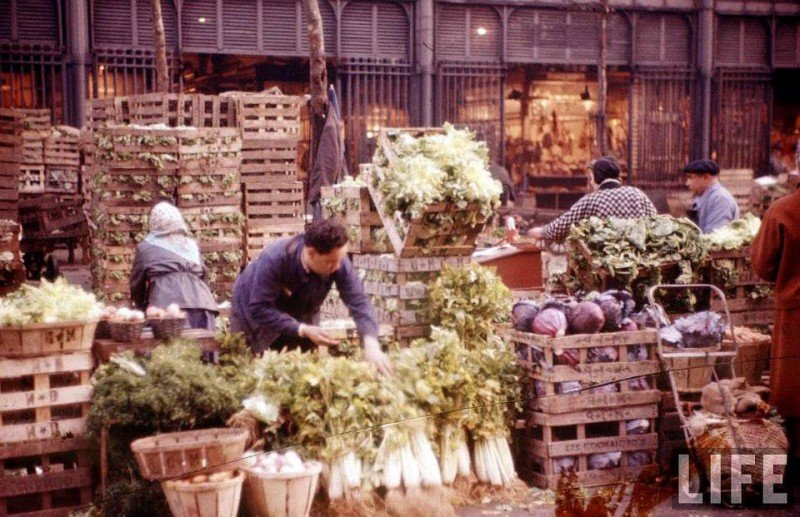

Below: These photographs taken by American Life photographer Thomas Mcavoy in 1956 were taken in the wee hours of the morning as the market was beginning to wind down from its most hectic shift. While the city slept, the meat and fish markets would go into full steam, trading and selling thousands of tons of wholesale produce in the middle of the night under the gigantic steel arches.

But it's the shellfish that truly showcases Sète's position on the Étang de Thau, one of the Mediterranean's great shellfish farming regions. Mountains of oysters—huîtres de Bouzigues—sit in wire baskets, sorted by size, their shells rough and barnacled. The famous Thau mussels, plump and sweet, fill crates by the dozens. Clams, cockles, sea urchins in season—the lagoon's bounty arrives here still smelling of salt water, often within hours of harvest. Vendors will shuck oysters on the spot, six for a few euros, with nothing but a squeeze of lemon. Stand at the counter and slurp them down while shoppers jostle past with their string bags growing heavy.

Beyond the seafood, Les Halles sprawls into a full market. Fruit and vegetable stands overflow with whatever is in season—fat tomatoes in summer, autumn squash, spring asparagus. Cheese vendors preside over wheels of Roquefort and creamy rounds of chèvre. The charcuterie counter offers pâtés, sausages, and terrines. Olive merchants tend barrels of olives cured a dozen different ways, their briny perfume cutting through the fish-scented air. There's a rotisserie chicken stand where birds turn slowly on spits, their skin lacquered golden. A bakery corner sells fougasse studded with olives or anchovies.

The market draws everyone: grandmothers with wheeled shopping carts who've been coming here for fifty years, young chefs from local restaurants inspecting the catch, tourists trying to decipher what they're looking at, and the vendors themselves, who seem to know half their customers by name. There's a democracy to it—no one gets special treatment, and if you don't know your fish, the vendors will educate you with a mixture of patience and mockery that's somehow affectionate.

By late morning, the frenzy begins to ebb. The best fish are gone. Vendors hose down their stalls, sweeping crushed ice and fish scales toward drains. The cacophony drops to a murmur. But even winding down, Les Halles pulses with life in a way that farmers markets in gentrified neighborhoods can't quite replicate. This isn't about artisanal products or sustainable brands—though the fish is certainly fresh and the oysters are farmed sustainably. It's about a town feeding itself, about commerce that predates tourism, about the elemental connection between boats and tables.

Walk out of Les Halles with a bag of oysters and a baguette, find a spot along the canal, and have yourself an impromptu feast. The oysters will taste like the lagoon—mineral and clean, with a sweetness that comes from weeks growing in the Thau's particular mix of salt and fresh water. This is Sète at its most essential: unglamorous, abundant, real. A town that still earns its living from the water, where the market isn't a tourist attraction but the beating heart of daily life, and where the line between sea and table is measured in hours rather than days.

Sète lingers long after you've left its canals behind. There's something about a place that hasn't been polished for visitors, that continues its daily rhythms whether you're watching or not, that makes it harder to shake. You'll remember the particular quality of light bouncing off the Grand Canal at dusk, the taste of oysters eaten standing at a market stall, the view from Mont Saint-Clair where sea and lagoon embrace a sliver of land that somehow became a town. Sète doesn't demand that you fall in love with it—the fishing boats will keep coming in, the joutes will happen every summer, Les Halles will open before dawn regardless of whether tourists discover it. But if you've paid attention, if you've wandered its bridges and climbed its stairs and lingered over its seafood, you'll find yourself thinking about return before you even realize it. Not because Sète is perfect—it's too real for that—but because it offers something increasingly rare: a Mediterranean port town that's still authentically itself, where the canals reflect not just buildings and sky but a way of life that the sea has shaped for more than three centuries. And once you've tasted that authenticity, once you've felt the particular pull of a place that belongs more to its people than to any guidebook, Sète becomes the kind of secret you want to keep and share in equal measure.